In Conversation With

Carl Magnusson on

Erwin Hauer

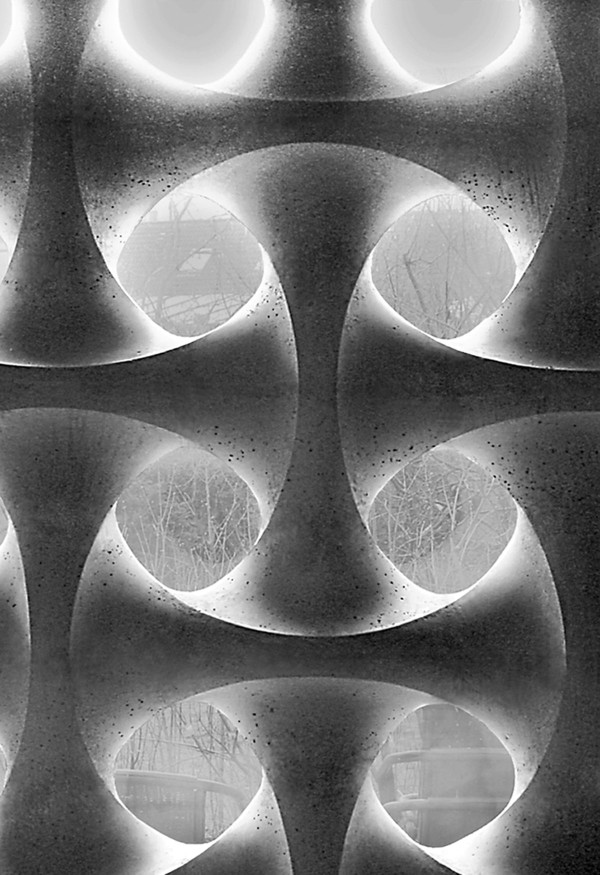

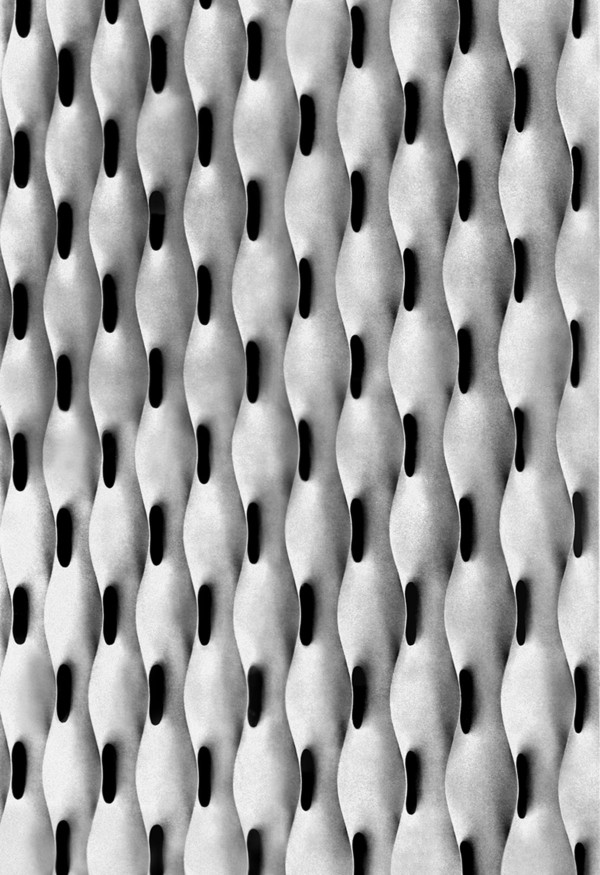

During the 1950s, architects and designers began taking a ‘less is more’ approach to interiors, prioritizing functionality over decoration. Architecture and furniture of the time marked a significant departure from previous ornamental styles and the advent of modernism. During this time, Austria-born sculptor Erwin Hauer began experimenting with sculpture that explored an infinite continuous surface, a style now considered ‘quintessential modernism.’

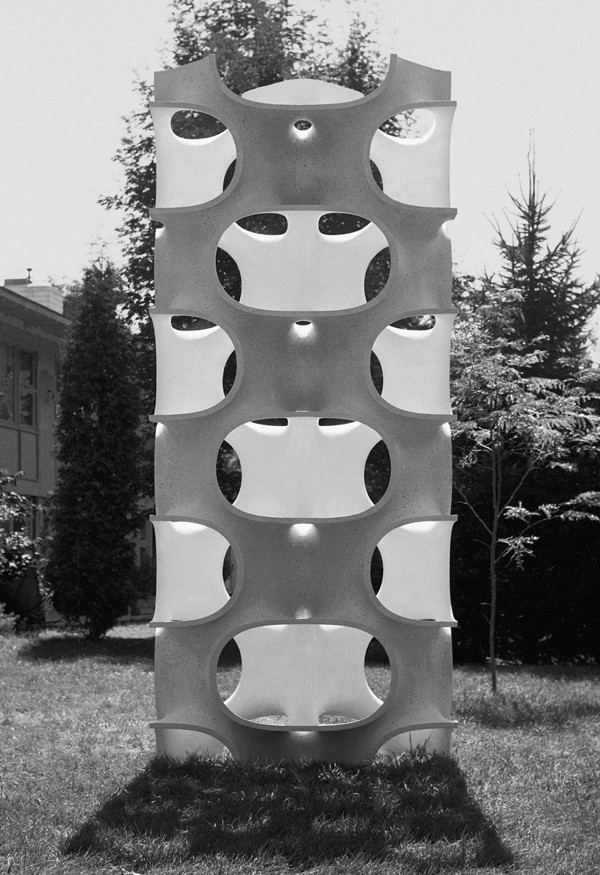

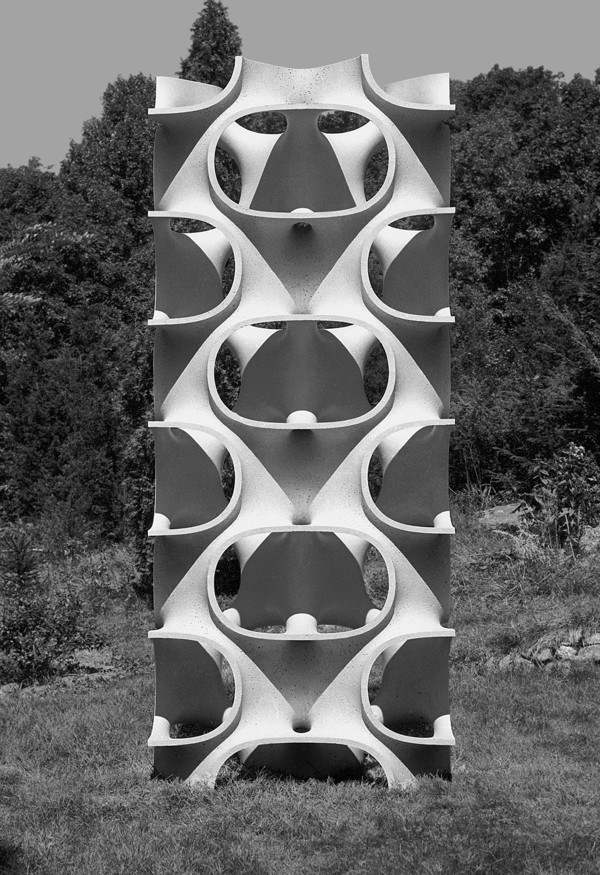

Hauer’s most iconic work and the installations we recognize today started as modular sculptures that explored repeating and complex patterns. These seemingly infinite patterns took shape as light-diffusing screens and walls that first appeared in churches in Vienna. These screens garnered attention abroad and resulted in a Fulbright scholarship that would bring Erwin Hauer to the United States in 1955, where he studied at the Rhode Island School of Design. Shortly after, he was invited by Josef Albers to join the faculty of Yale University, where he taught until 1990.

In 2004, following the publication of Erwin Hauer: Continua, Architectural Screens, and Walls, there was a renewed demand for Hauer’s modular screens. Hauer and a former student worked to produce some of his earliest designs for installation at some of the most recognized cultural institutions across the U.S., including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Standard Hotel in New York City.

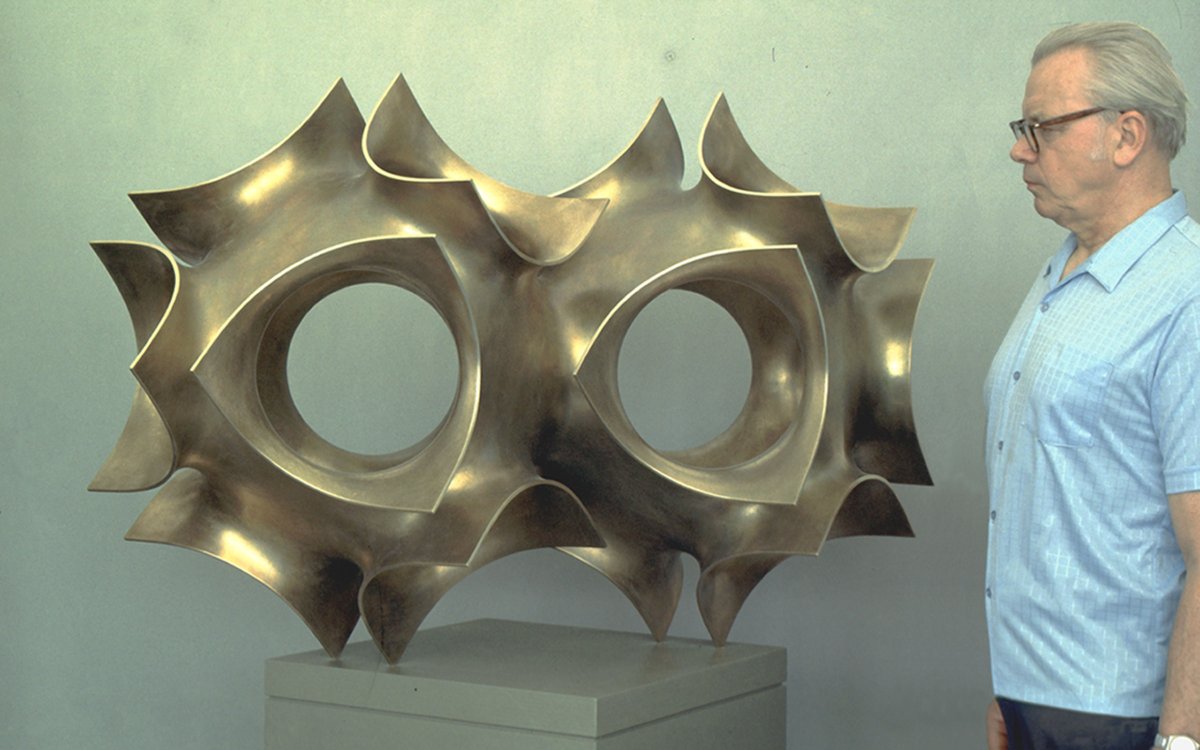

Seeing over a decade of success, Hauer remained dedicated to his work as an independent sculptor in Bethany, Connecticut. During this time, he delved into various designs and prototypes, focusing exclusively on saddle surfaces, a field of studies to which Hauer made significant contributions.

“One thing that I thought is extremely important in sculpture is the concept of space and time. There is an element of time in anything three-dimensional. Something has to change in significant ways when you change your vantage point in space. When you merely move any three-dimensional object, that may not be enough in some cases. It’s the difference between noise and music. You want something that transcends the merely visible.”

“Some of my license to do repeat patterns comes from the continual in Baroque music, which is the recycling of a theme. The essence of the composition is interwoven with it, but the continual is what supports that structure.”

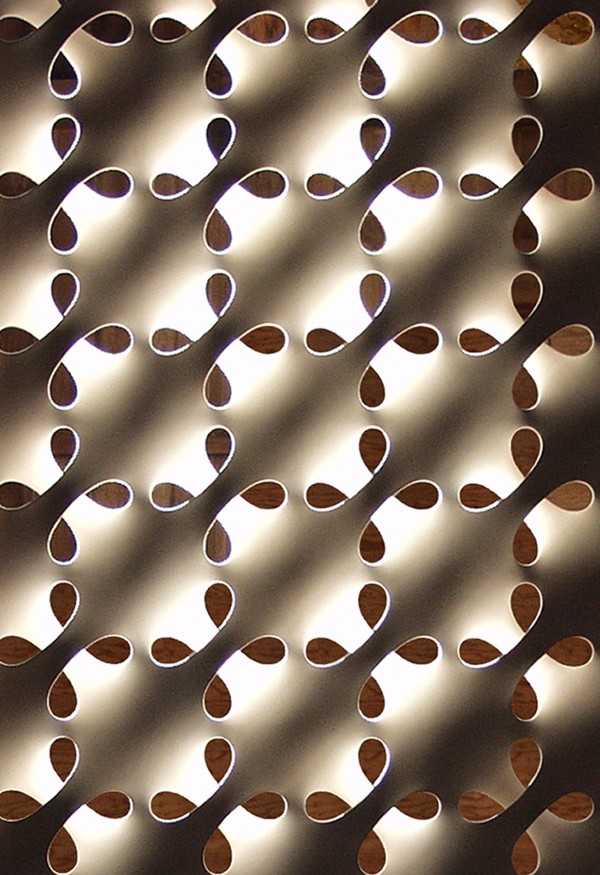

In 2020, Spinneybeck | FilzFelt worked with Erwin Hauer Studios to reimagine his iconic designs through a series of inspired hanging panels. With an ongoing effort to revitalize his work, Spinneybeck continues to celebrate the late designer’s work with a new take on a familiar favorite – Design 406.

Former Creative Director at Knoll, Carl Gustav Magnusson, had the pleasure of unearthing Erwin’s life’s work and immense collection of sculptures and prototypes. Carl has spent the last year delving through the artist’s work, examining a range of prototypes through the lens of modern technology. We chatted with Carl about the surprising finds among Hauer’s archives, the impact this designer continues to have on the architectural world, and what makes his work so timeless.

Can you speak briefly about Erwin Hauer’s work and his impact on the design world?

Owing to the relative obscurity of Erwin Hauer’s creativity, I think his work has yet to achieve the impact it deserves. While he was exceedingly productive, the complexity of his concepts took time to manifest due to the limitations of technology at the time. Extraordinarily prolific, he generated more ideas than could manifest into reality at that time. We are the grateful heirs to these thoughts.

When Erwin came to the U.S., he brought with him “a big load of modules and molds of my designs,” which garnered the attention of Arthur Drexler and Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., two curators with the Museum of Modern Art. They referred him to several architects, including Florence Knoll, Philip Johnson, Welton Beckett, Max Abromowitz and Marcel Breuer.

You were the design director at Knoll for over thirty years when many of Erwin’s screens were installed in various showrooms. Can you discuss Erwin’s relationship with Florence Knoll? Were there other designers with whom he had a notable connection at that time? Can you touch on his relationship with Knoll?

Unfortunately, I was not involved in any of the projects as I started at Knoll in 1975 and left in 2005. Florence Knoll was the initial contact, which resulted in several installations, including First National Bank in Miami, Knoll International de Mexico in Mexico City, and LOOK magazine in New York. After Florence’s retirement, Karen Stone, Head of Showroom Design, rediscovered Erwin’s work in 2006 and installed it in the Chicago Knoll showroom.

His relationship with Knoll was project-based― when a showroom specified his work, it was fabricated and installed. To my knowledge, his work was not offered as a product until now owing to the manufacturing complexities, which have now been overcome.

You’ve mentioned his work’s timelessness and enduring aesthetics because of its deeply rooted relationship to basic mathematics and geometries. Can you speak more about this?

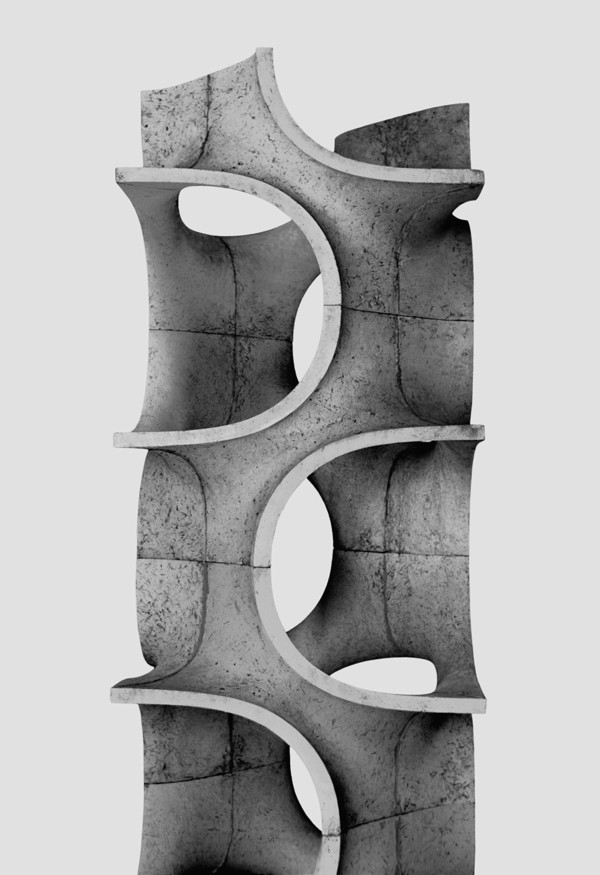

Unlike his contemporaries, such as Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, who were inspired by the human body and natural forms, Erwin was driven by his fascination with geometric forms based on Euclidean principles. He explored the visual complexity of mathematical shapes into three-dimensional shapes. I think this proves how enduring the aesthetic of his work is. Because his work is rooted in basic mathematics and geometry, it will always be timeless, always be in style, and always be beautiful.

You’ve also touched on the relationship between his designs, light, and the materials with which they’re constructed. With the launch of Design 406 in both wood and leather, can you speak a bit more about this?

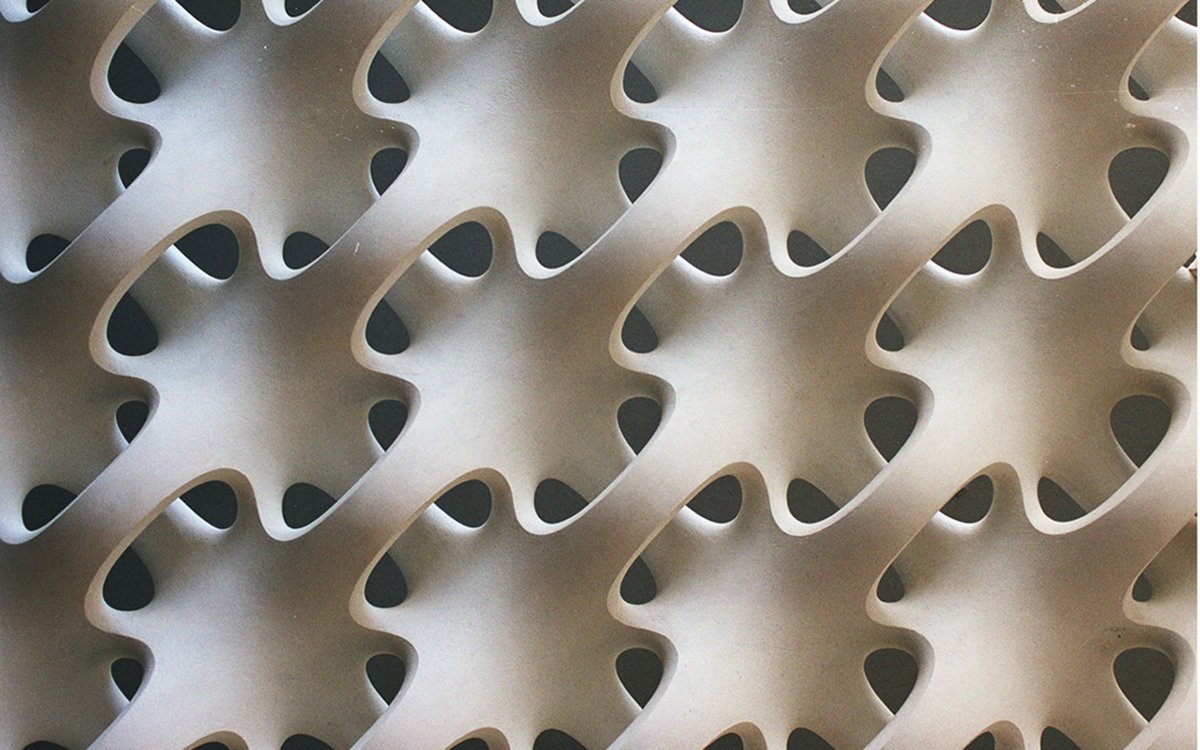

The very nature of his dimensional designs is impacted by material and light. Hauer explored a wide range of materials throughout his career, from gypsum to marble and bronze, so the unique materials he chose combined with the light-diffusing designs themselves have an unmatched atmospheric impact. His work’s repeated and curved lines play with light and shadow in such an exciting way.

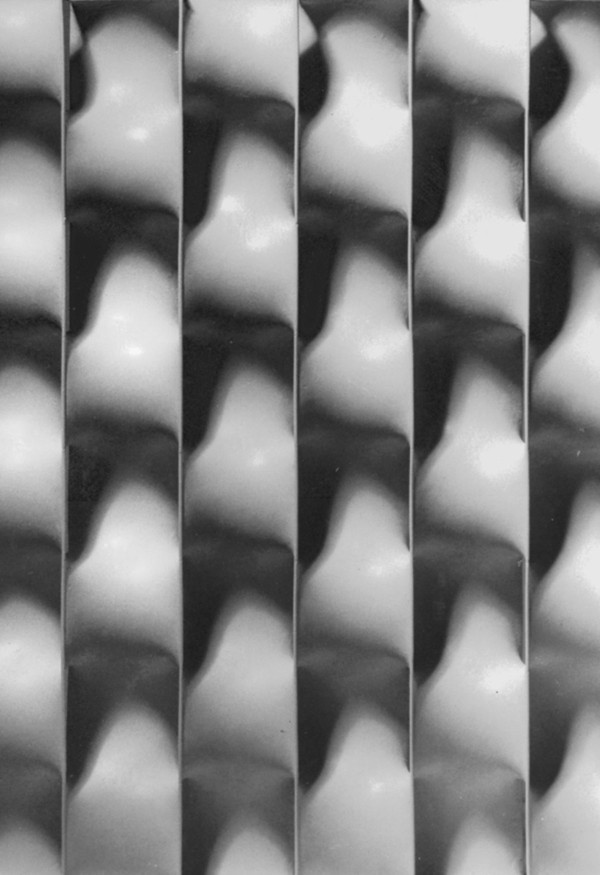

Hauer took great advantage of this, as witnessed by Design 406. The undulating lines, with their deep crevasses, explore this opportunity. As you walk past these panels or as the quality and direction of light change throughout the day, the experience is a very positive and evolving one. Add to that the sensuous beauty of the material, whether it is the inherent attraction of natural oak grain or the natural attraction to the color and textures of Spinneybeck leather.

"Erwin was driven by his fascination with geometric forms based on Euclidean principles. He explored the visual complexity of mathematical shapes into three-dimensional shapes. I think this proves how enduring the aesthetic of his work is. Because his work is rooted in basic mathematics and geometry, it will always be timeless, always be in style, and always be beautiful."

On the topic of light, Design 406 stands out among his body of work, particularly for its absence of perforations. This stands in stark contrast to his other designs, which served as light-diffusing screens. This design, however, has a very different relationship with light. The light no longer shines through but rather reflects only on the surface. Can you speak about this departure from his previous work?

I view Design 406 not as a departure but as an enhancement of his previous works. It still plays with light and shadow, and that relationship changes as the light does throughout the day.

As you’ve explored the archives, what are some of the most exciting and captivating works you’ve come across? Could you share some of your favorite discoveries and what makes them so intriguing?

As we uncover the trove of designs, we are taken by the breadth and depth of his sculptures. His exploration of materials ranging from common gypsum through cast bronze to hewed marble exhibits his mastery of materials applied to geometric shapes. His “TURM” piece of 1968 is of particular interest as it exemplifies his “Infinite Surface I-WP” exploration into countless planes of infinity.

"Hauer explored a wide range of materials throughout his career, so the unique materials he chose combined with the light-diffusing designs themselves have an unmatched, atmospheric impact. His work’s repeated and curved lines play with light and shadow in such an exciting way."

You’re sorting through his designs and archives and really seeing this body of work through the lens of modern technology. Can you tell us a little about his work from this perspective?

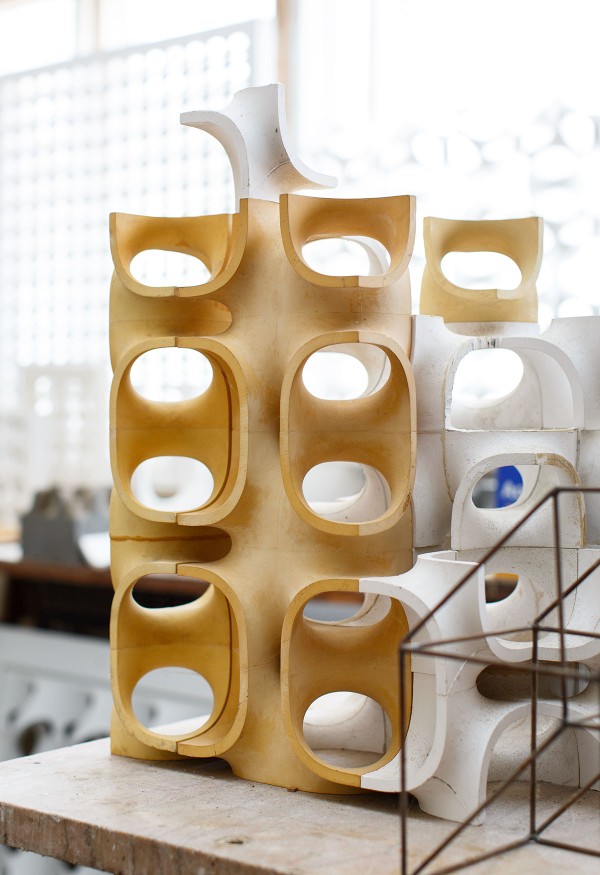

Most of Erwin Hauer’s designs were stalled at the prototyping stage. His work was ahead of practical manufacturing techniques, so many of his hand-made sculptures and prototypes could only progress so far. Now, half a century later, a variety of new manufacturing techniques are available to us, and more will come in the ensuing years.

New processes such as 3D printing allow us to make one-offs of his designs, but they have yet to be a commercially viable solution. His designs, however, were founded on mathematical principles, so they lend themselves well to CAD technology and can therefore be more easily scaled.

The technology available today wasn’t around when Erwin created these remarkable prototypes. Can you share some insight into what viewing his work through this lens looks like?

With the advent of digitizing in the late 1970s, the process of converting analog data into a digital format, combined with computer-aided design (CAD), and now with 3D printing, it is possible to 3D print a facsimile of his work or CNC machine various materials. The limitations continue to be size, material and production capacity. Fortunately, Design 406 lends itself well to CNC machining of solid wood.

Erwin Hauer seemed to express that artists shouldn’t be overly reliant on technology.

“Many of the young readers of Continua seemed Surprised, even incredulous, to learn that I was able to accomplish what I did without any electronic help. They have become so dependent upon and, ultimately, so limited to electronic life support that they could be seriously hindered when the battery quits. Perhaps then they will be encouraged to trust their own minds once again when they see proof from my work that it can be done.

The computer is a marvelous tool, but it does not always know best. Like hammer and chisel, this contemporary tool helps us carry out our ideas, but it does not supply those ideas. If my work contributes in some measure to this realization, I’ll be proud.”

In today’s world, we find a lot of interest in generative AI and next-generation production technologies. Do you think he would have been drawn to these precisely because some can help and enable you to create infinite surfaces, generating tiled patterns from a single image? Or do you think he would have been opposed to these technological developments?

He certainly relied on his imagination for his original ideas. Still, Erwin used modern tools and technology to manifest them into sculpture, so I think he would have been open to the idea and invited AI technology. Since his work is based on scientific interpretation, he would have likely been intrigued by what’s possible today. I imagine he would have been open to using AI to a certain extent, perhaps as a means of editing original ideas.

What makes Spinneybeck a good fit for Erwin’s work?

Spinneybeck has evolved into an open-minded facilitator of architectural surfaces and finishes. Its ability to experiment and develop products with cutting-edge processes and materials has led to breakthrough designs that were previously impossible. With this collaboration, as Erwin originally conceived, Hauer’s designs and prototypes will finally be manufactured and made commercially available.

What excites you most about seeing this launch of Design 406? What do you look forward to seeing in the future?

I’m most excited to reignite Erwin Hauer’s brilliant work to the cultural recognition it deserves and into commercial reality, as he wished. This process has been and continues to be a fascinating professional journey that I am proud and enthusiastic to be a part of.